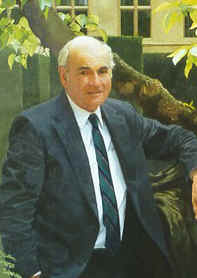

Baruch S. Blumberg

(1917 - 2003)

I was born in 1925, in New York City, the second of three children of Meyer and Ida Blumberg. My grandparents came to the United States from Europe at the end of the 19th century. They were members of an immigrant group who had enormous confidence in the possibilities of their adopted country. I received my elementary education at the Yeshiva of Flatbush, a Hebrew parochial school, and, at an early age, in addition to a rigorous secular education, learned the Hebrew Testament in the original language. We spent many hours on the rabbinic commentaries on the Bible and were immersed in the existential reasoning of the Talmud at an age when we could hardly have realized its impact.

After attending Far Rockaway High School I joined the U.S. Navy in 1943 and finished college under military auspices. I was commissioned as a Deck Officer, served on landing ships, and was the commanding officer of one of these when I left active duty in 1946. My interest in the sea remained. In later years I made several trips as a merchant seaman, held a ticket as a Ships Surgeon, and, while in medical school, occasionally served as a semiprofessional hand on sailing ships. Sea experience placed a great emphasis on detailed problem solving, on extensive planning before action, and on the arrangement of alternate methods to effect an end. These techniques have application in certain kinds of research, particularly in the execution of field studies.

My undergraduate degree in Physics was taken at Union College in upstate New York, and in 1946 I began graduate work in mathematics at Columbia University. My father, who was a lawyer, suggested that I should go to medical school, and I entered The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University in 1947. I enjoyed my four years at the College immensely. Robert Loeb was the chairman of the Department of Medicine and exerted a marked influence on the entire college. There was a strong emphasis on basic science and research in the first two years (we hardly saw a patient till our third year), and we learned practical applications only in our last years.

Between my third and fourth years, Harold Brown, our professor of parasitology, arranged for me to spend several months at Moengo, an isolated mining town, accessible only by river, in the swamp and high bush country of northern Surinam. While there we delivered babies, performed clinical services, and undertook several public health surveys, including the first malaria survey done in that region. Different people had been imported into the country to serve as laborers in the sugar plantations, and they, along with the indigenous American Indians, provided a richly heterogeneous population. Hindus from India, Javanese, Africans (including the Djukas, descendants of rebelled slaves who resided in autonomous kingdoms in the interior), Chinese, and a smattering of Jews descended from 17th century migrants to the country from Brazil, lived side by side. Their responses to the many infectious agents in the environment were very different. We were particularly impressed with the enormous variation in the response to infection with Wuchereria bancroftia (the filariad which causes elephantiasis), and my first published research paper was on this topic. This experience was recalled in later years when I became interested in the study of inherited variation in susceptibility to disease. Nature operates in a bold and dramatic manner in the tropics. Biological effects are profound and tragic. The manifestations of important variables may often be readily seen and measured, and the rewards to health in terms of prevention or treatment of disease can be great. As a consequence, much of our field work has been done in tropical countries.

I was an intern and assistant resident on the First (Columbia) Division at Bellevue Hospital in lower New York from 1951 to 1953. It is difficult to explain the fascination of Bellevue. In the days before widespread health insurance, many of the city's poor were hospitalized at Bellevue, including many formerly middle class people impoverished by the expenses of chronic illness. The wards were crowded, often with beds in the halls. Scenes on the wards were sometimes reminiscent of Hogarth's woodcuts of the public institutions of 18th century London. Despite this, morale was high. We took great pride that the hospital was never closed; any sick person whose illness warranted hospitalization was admitted, even though all the regular bed spaces were filled. A high scientific and academic standard was maintained. Our director, Dickinson W. Richards, and his colleague, André F. Cournand, received the Nobel Prize for their work on cardio-pulmonary physiology. Anyone who has been immersed in the world of a busy city hospital, a world of wretched lives, of hope destroyed by devastating illness, cannot easily forget that an objective of big-medical research is, in the end, the prevention and cure of disease.

I spent the following two years as a Clinical Fellow in Medicine at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center working in the Arthritis Division under Dr. Charles A. Ragan. I also did experimental work on the physical biochemistry of hyaluronic acid with Dr. Karl Meyer. From 1955 to 1957, I was a graduate student at the Department of Biochemistry at Oxford University, England, and a member of Balliol College. I did my Ph.D. thesis with Alexander G. Ogston on the physical and biochemical characteristics of hyaluronic acid. Professor Ogston's remarkable combination of theory and experiment guided the scientific activity in his laboratory. He has served as a model to me on how to train students; I hope I have measured up to his standard. Sir Hans Krebs was the chairman of the Department of Biochemistry. I have profited by conversations with him, particularly when (in 1972) I was a visiting fellow at Trinity College and we had opportunities to discuss our mutual interests in the history of science.

Oxford science at that time was influenced by the 19th and 20th century British and European naturalists, scientists and explorers who went to the world of nature - often to distant parts of it - to make the observations which generated their hypotheses. Anthony C. Allison was then working in the Department of Biochemistry and introduced me to the concept of polymorphism, a term introduced by the lepidopterist E. B. Ford of the Department of Zoology. In 1957 I took my first West African trip (to Nigeria) and was introduced to the special excitement of that part of the world. I found the Nigerians warmhearted and friendly with a spontaneous approach to life. We collected blood specimens from several populations (including the nomadic pastoral Fulani and their domestic animals) and studied inherited polymorphisms of the serum proteins of milk and of hemoglobin. This approach was continued in many subsequent field trips, and it eventually led to the discovery of several new polymorphisms and, in due course, the hepatitis B virus.

I worked at the National Institutes of Health from 1957 until 1964. This was during a period of rapid growth for the NIH, and I continued to develop my research on polymorphisms and their relation to disease. This led to the formation of the Section on Geographic Medicine and Genetics, which was eventually assigned to an epidemiology branch directed by Thomas Dublin, from whom I learned the methods of epidemiology. The NIH was a very exciting place, with stimulating colleagues including J. Edward Rall, Jacob Robbins, J. Carl Robinson, Kenneth Warren, Seymour Geisser, and many others. The most important connection I made, however, was with W. Thomas London (who later came to The Institute for Cancer Research), who has become a colleague, collaborator, and good friend with whom I have worked closely for fifteen years. Tom was an essential contributor to the work on Australia antigen and hepatitis B, and without him it could not have been done.

I came to The Institute for Cancer Research in 1964 to start a program in clinical research. The Institute was, and is, a remarkable research organization. Our director, Timothy R. Talbot, Jr., has a deep respect for basic research and a commitment to the independence of the investigators. Above all, people are considered an end in themselves, and the misuse of staff to serve some abstract goal is not tolerated. Jack Schultz was a leading intellectual force in the Institute, and his foresighted, humane view of science, his honesty and his good sense influenced the activities of all of us. Another important characteristic is the dedication and intelligence of our administrative and maintenance staffs, which contributes to the strong sense of community which pervades our Institute.

Over the course of the next few years we built up a group of investigators from various disciplines and from many countries (Finland, France, Italy, Poland, Venezuela, England, India, Korea, China, Thailand, Singapore) who, taken together, did the work on Australia antigen. Alton I. Sutnick (now Dean of the Medical College of Pennsylvania) was responsible for much of the clinical work at Jeanes Hospital. Some of the early workers included Irving Millman, Betty Jane Gerstley, Liisa Prehn, Alberto Vierucci, Scott Mazzur, Barbara Werner, Cyril Levene, Veronica Coyne, Anna O'Connell, Edward Lustbader, and others. There were many field trips during this period to the Philippines, India, Japan, Canada, Scandinavia, Australia, and Africa. It has been an exciting and pleasant experience surrounded by stimulating and friendly colleagues.

At present, we are conducting field work in Senegal and Mali, West Africa, in collaboration with Professor Payet of Paris, formerly the Dean of the Medical School of Dakar, with Professor Sankalé, his successor in Dakar, and a group of other French and Sengalese colleagues, including Drs. Larouzé and Saimot.

I am Professor of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and attend ward rounds with house staff and medical students. I am also a Professor of Anthropology and have taught Medical Anthropology for eight years. I have learned a great deal from my students.

My non-scientific interests are primarily in the out-of-doors. I have been a middle distance runner (very non-competitive) for many years and also play squash. We canoe on the many nearby lakes and rivers of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. I enjoy mountain walking and have hiked in many parts of the world on field trips. With several friends we own a farm in western Maryland which supplies beef for the local market. Shoveling manure for a day is an excellent counterbalance to intellectual work.

My wife, Jean, is an artist who has recently become interested in print making. We have four children of whom I am very proud: Anne, George, Jane, and Noah. They are all individualists, which makes for a turbulent and noisy household, still we miss the two oldest who are now away at college. We live in the center of old Philadelphia, a few blocks from Independence Hall. The city has appreciated its recognition by the Nobel Award in our Bicentennial Year.

From Les Prix Nobel en 1976, Editor Wilhelm Odelberg, [Nobel Foundation], Stockholm, 1977

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/Nobel Lectures. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Courtesy of:

http://nobelprize.org/medicine/laureates/1976/blumberg-autobio.html