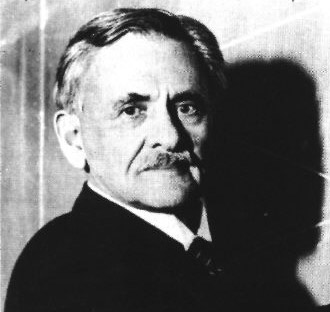

Albert

Abraham

Michelson

(1852 - 1931)

Born in Strelno, Prussia (later Strzelno, Poland), son of a Jewish merchant, Michelson was brought to America as a small child. He grew up in the rough, booming mining towns of Murphy's Camp, California and Virginia City, Nevada. In 1869 he went to Annapolis as an appointee of President U. S. Grant. After graduation he stayed on at the Naval Academy as a science instructor.

A single event in November 1877 stamped a pattern on his life. While preparing a lecture demonstration of Foucault's method for determining the velocity of light, Michelson realized that if he collimated the beam he could get a much longer optical path-length and thus a great increase in sensitivity. In the next two years he did the experiment, aided by his enthusiasm and mechanical talent, and also by a grant from his father-in-law, amounting to $2000 (the equivalent of ten times as much today). Encouraged by success and by the advice of the prominent astronomer Simon Newcomb, Michelson resolved on a career in physics. He went to Europe for two years of study.

At Helmholtz's laboratory in Berlin Michelson designed and built a fundamental experiment. He had in mind a new sort of interferometer, sensitive enough to measure the second-order effects depending on the velocity of the earth's motion through the ether—that odd, stiff fluid which physicists of the day required as a medium to carry the vibrations of light. Michelson got a null result, and was disappointed. He felt that he had failed to measure the ether.

In 1882 he took a position at the Case School of Applied Science, the first of a series of positions at newly-founded science schools. He collaborated with the respected chemist Edward Morley in several researches, of which the most important was a repeat, now far more sensitive, of the Berlin experiment. Morley, a skilled experimentalist, made major contributions to the design and execution. The result was another discouraging "failure"; it seemed impossible to detect any motion through the ether. This experiment of Michelson and Morley was quickly recognized as the most striking and significant of several different kinds of attempts to measure the ether, which together prepared the ground of doubts and opinions among European physicists from which Einstein's theory of relativity sprang. Michelson later acknowledged the importance of Einstein's work, but to the end of his life he could never believe that light was not a vibration in some sort of ghostly ether. For more, visit our page on Einstein's discoveries.

In 1889 Michelson went to Clark University, and three years later moved on to become the head of the physics department at the University of Chicago, newly erected on a solid foundation of Rockefeller money. Both schools were struggling to guarantee scientists enough funds and time for pure research, while not neglecting education. As a teacher Michelson was aloof and forbidding, but lucid. In the course of his painstaking and exhausting researches and a difficult first marriage he had developed reserve and self-restraint. Still he was able to help physics teaching and research flourish at Chicago, and he was among the founders of The American Physical Society, becoming its second president.

For many years he labored to make diffraction gratings better than Henry Rowland's. But he was better known as the man who measured the International Meter in Paris against the wavelength of cadmium light; as the first American scientist to win a Nobel Prize (1907); and as the first person to measure the angular diameter of a star, which he did at the age of 67 with one of his beloved interferometers. His most sustained efforts went into surpassing his own classic measurements of the velocity of light. In 1926 he did this on a 22-mile baseline, within an uncertainty of +/-4 km sec-l. Five years later he tried another measurement, now in an evacuated pipe a mile long, and died as he was writing up his results.

In the nineteenth century, while physics lagged in the United States, American engineers and inventors had already become the equals or superiors of any in the world. American physicists felt the influence of this tradition, drawing on engineering and inventive skills in their pursuit of fundamental problems. The result can be seen in its most beautiful form in the Michelson-Morley apparatus, which managed to be at the same time ingenious and straightforward, massive and exquisitely delicate.

Courtesy of: